Volatile in Java

Recently, there is a very interested topic bringing up in my desk: What is Volatile in Java? Some guys in my team are saying that Volatile is used for keeping one copy in memory to avoid duplicate object in stack since Modern CPU has multiple cores and each of them has its own cache of the copy, and some others are arguing that Volatile is same as synchronized.

Hnn…I have to say none of them has the full picture of Volatile in Java and how it works. But before I show the world of Volatile, I would like to introduce something else.

Heap vs. Stack

In Java land, All the multi-threaded issues are doing racing between the data. Everyone(means every thread) wants the data exclusive so that it can be kept safely and be clean to other threads. So the data itself is the source of everything. How we stored the data in Java is the keypoint to learn before we know Volatile or even Synchronized.

Java is using Heap and Stack to store all the data it wants, including the program itself.

Heap

Java Heap space is used by Java runtime to allocate memory to objects. Whenever we create any object, it’s always created in Heap space.

Stack

Java Stack is used for execution of a thread. They contain method specific values such as local variable, method parameters and so on which are short lived and references to other objects in the heap that are getting referred from the method. Actually, the Java Stack is the model of Java program execution which I will talk later in another topic.

Difference?

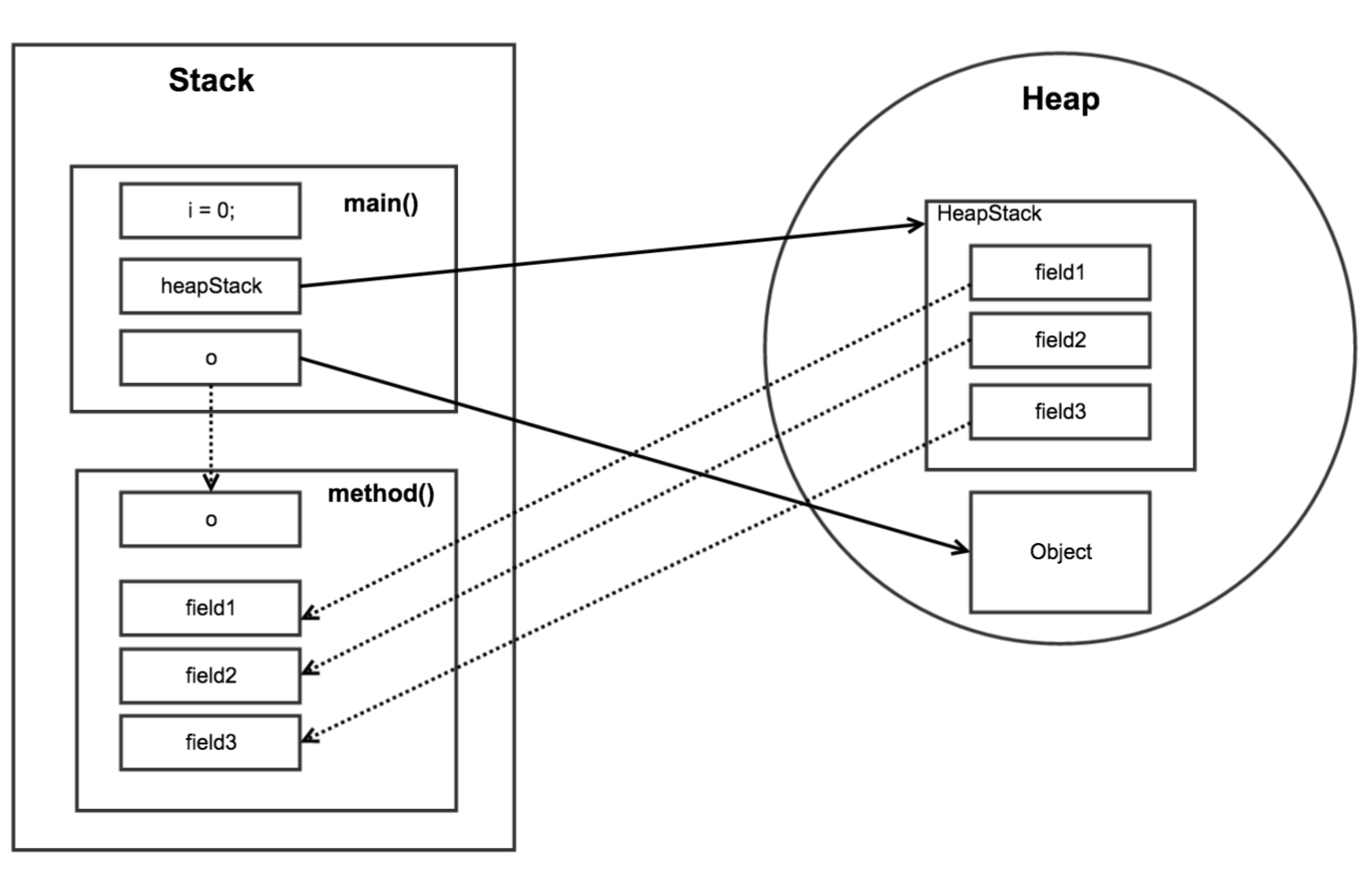

However, it’s not figurative that just saying in words. Let’s understand the Heap and Stack memory usage with a simple program.

public class HeapStack {

private int field1 = 1;

private int field2 = 2;

private int field3 = 3;

public static void main(String[] args) {

int i = 0;

HeapStack heapStack = new HeapStack();

Object o = new Object();

heapStack.method(o);

}

private void method(Object o) {

field1++;

field2++;

field3++;

}

}

And pls keep in mind: All the objects are created in Java Heap, and the Stack is only keeping the references to them. So the statement Object o = new Object(); actually creates the object in Heap space, and 4 bytes(32-bit system) memory in Stack to store the address of the object(not the object itself, but just the reference).

That’s a simple introduction of Java Heap and Stack. There are ten thousands of other topics online to summarize them if you want to learn more. The thing we talked above is enough for you to keep continuing.

What’s the problem that Volatile try to solve?

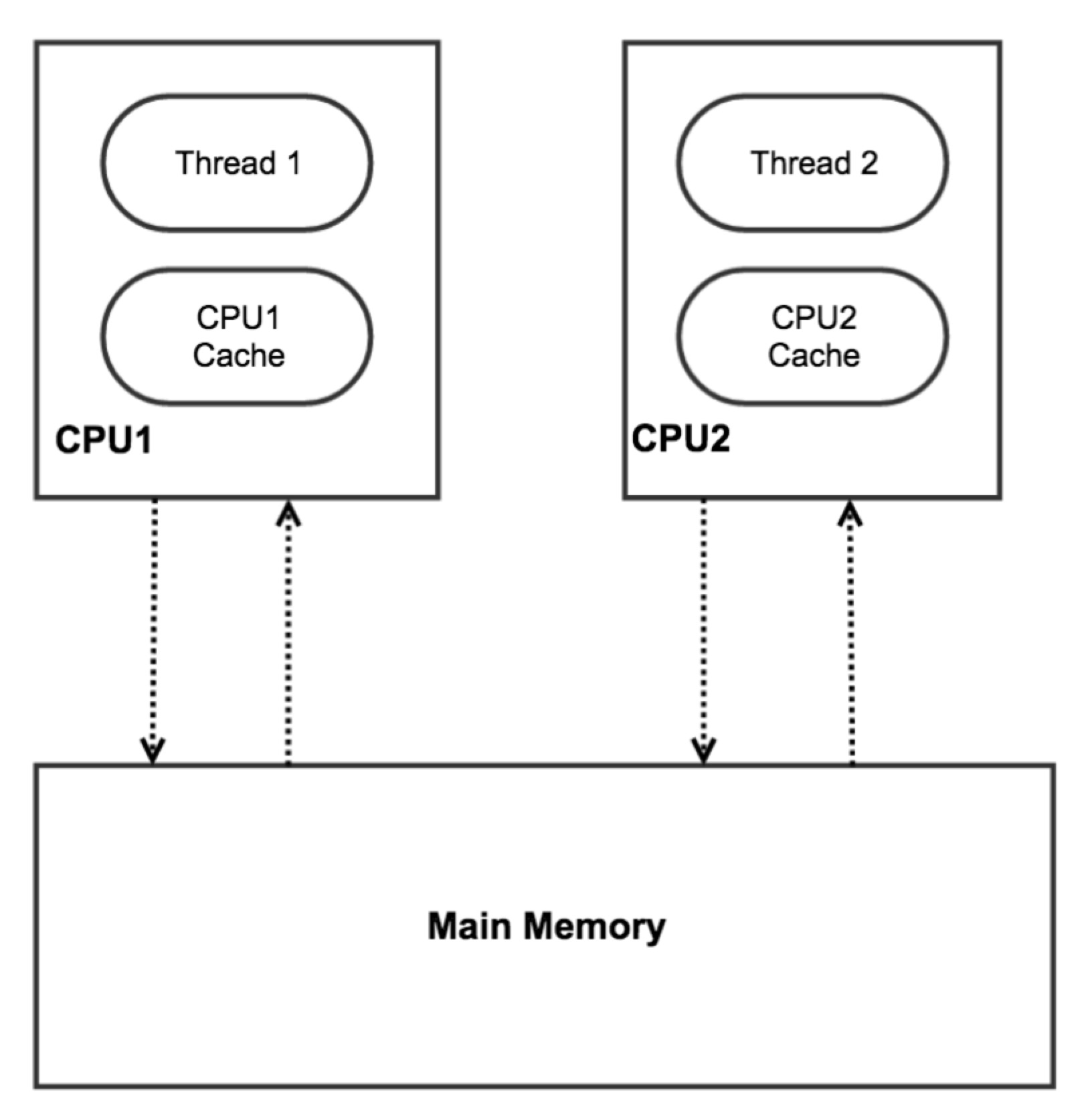

In Java application, multiple threads can run parallel in different CPUs if the system does have. Due to the performance reasons, each thread may copy variables from main memory into a CPU cache while working on them.

So now here is the problem: Without Volatile there are no guarantees about when the JVM reads data from main memory to CPU caches or write data from CPU caches to main memory.

Let’s take one example.

public class ShareObject {

public int count = 1;

}

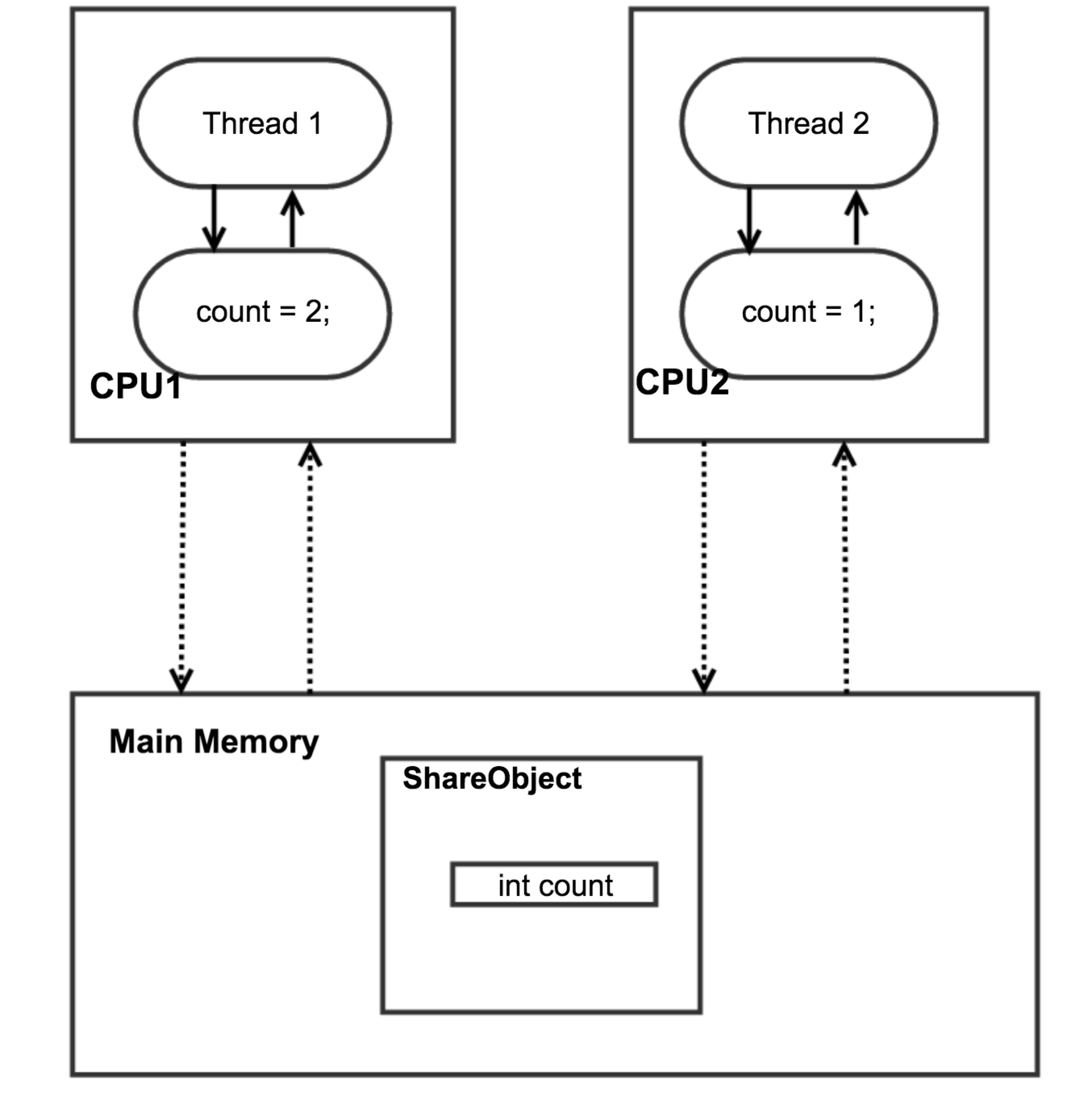

There are two threads in our app, thread 1 increments the count variable, but both thread 1 and 2 read the count variable from time to time.

If the variable of count is not declared as volatile, there is no guarantee that when the value of count is written from the CPU cache in thread 1 back to main memory. That means, the count variable value in CPU cache may not be same as main memory like below.

The problem with threads not seeing the latest value of a variable because it has not yet been written back to main memory by another thread, is called a “visibility” problem. The updates of one thread are not visible to other threads.

By declaring the count variable volatile all writes to the count variable will be written back to main memory immediately. Also, all reads of the count variable will be read directly from main memory. Here is how the volatile declaration of the count variable looks:

public class ShareObject {

public volatile int count = 1;

}

So the key point is if the variable will be both written and read in different threads, then you need to worry about the visibility problem. In another word, if all the threads just read the variable, it doesn’t need the volatile.

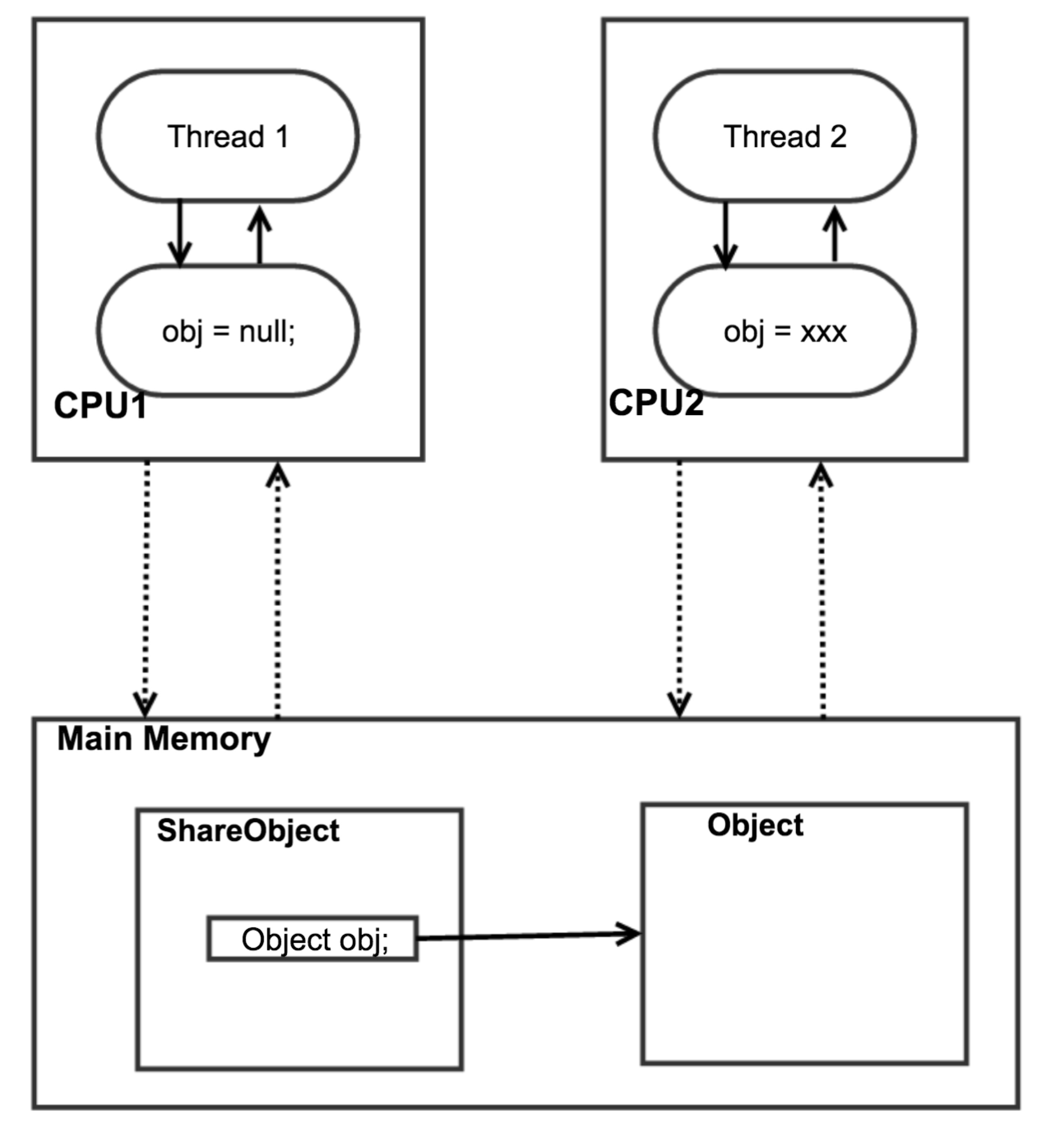

The modifier volatile is added ahead of any instance field which means it should support both primitive type and Java object. As we already went through the usage on primitive type, let’s talk about what’s going on if the volatile is put on ahead of instance object field.

public class ShareObject {

public Object obj = new Object();

}

Actually, the behavior is same as primitive type. You can think value of the obj in the cache is the memory address which will point to the real memory in heap space. So if there is no volatile, thread 1 changes the value of obj to Null but thread 2 is still operating the old object.

By declaring the obj volatile, all writes to the obj reference will be flushed back to main memory immediately. And all other CPU caches with obj will be updated immediately so that they can keep operating on same object.

Extra gurantees of Java volatile

Since Java 5 the volatile keyword can bring more gurantees than just reading and writing to main memory variable. That is:

- If the thread 1 writes to a

volatilevariable and thread 2 read this variable sequentially, then thevolatilecan gurantee that all variables beforevolatilevariable will also be visible to thread 2. - The reading and writing instruction of a

volatilevariable will NOT be re-ordered by JVM. In the modern CPU infrastructure the instructions could be re-ordered to improve the performance. E.g.,

obj.nonVolatile1 = 1;

obj.nonVolatile2 = 2;

obj.nonVolatile3 = 3;

obj.nonVolatile4 = 4;

obj.nonVolatile5 = 5;

It will be re-ordered like this:

obj.nonVolatile1 = 1;

obj.nonVolatile2 = 4;

obj.nonVolatile3 = 3;

obj.nonVolatile4 = 2;

obj.nonVolatile5 = 5;

The first gurantee is easy to understand. For instance,

Thread 1:

obj.nonVolatile = 1;

obj.count = 2;

Thread 2:

int count = obj.count;

int nonVolatile = obj.nonVolatile;

Since the nonVolatile is written before volatile variable count, so it will be also visiable to Thread 2 who reads the volatile variable count at very beginning.

The second gurantee is not easy to understand. Let’s use one detail example to explain it:

obj.nonVolatile1 = 1;

obj.nonVolatile2 = 2;

obj.volatile = 3;

obj.nonVolatile4 = 4;

obj.nonVolatile5 = 5;

After the instructions are re-ordered:

obj.nonVolatile2 = 2;

obj.nonVolatile1 = 1;

obj.volatile = 3; // a volatile variable

obj.nonVolatile5 = 5;

obj.nonVolatile4 = 4;

The JVM may re-order the first two instructions as long as them happens before the volatile write instruction. Similarly, the JVM may re-order the last two instructions as long as the volatile instruction happens before them.

Volatile is the minimum but far from enough

Even the volatile can gurantee all the reads of volatile variables are reading directly from main memory, and all the writes to volatile variables are writting directly into main memory, but there is still one thing it cannot gurantee - Race Condition, which we have to use another powerful kits provided by Java SDK - synchronized and concurrency package. That’s another topic I want to introduce later, such as the internal mechanism and implementation of synchronized inside JVM, and what CAS means, and why it is the foundation of whole concurrency package.

Let’s see one simple Race Condition problem.

volatile int count = 0;

Thread 1:

obj.count++;

Thread 2:

obj.count++;

You will expect that the count should equal to 2 after doing increment by both thread 1 and 2. But the truth is you may get count equals to 1.

volatile is not working in this case because the count++ in JVM could be compiled as below instructions:

int temp = obj.count; //load count into local

temp = temp + 1; //increment

obj.count = temp; //store back into main memory

Since there are three instructions over here, thread 1 and 2 will be very possible to execute the first instruction at the same time(both of them read 0 from main memory). And then after instructon 2 and 3, the count will become to 2 instead of the 3 which we expect.

So the problem is volatile cannot solve the problem of Race Condition. It can only gurantee the int temp = obj.count and obj.count = temp are keeping align with each other, but what we want gurantee here is that the three instructions should be accessed by only one thread in same time.

Something interesting

Recently, our team members have a long discussion of below story. Actually, the story is very simple. I will summarize it shortly.

There are two methods in the class, and they may be called by different thread. Both of them need to access a lock and synchronize it. Here is the thing:

public class ShareObject {

private final Object lock = new Object();

public void methodA() {

...

synchronized(lock) {

...

}

...

}

public void methodB() {

...

synchronized(lock) {

...

}

...

}

}

Two threads running parallel:

Thread 1:

obj.methodA();

Thread 2:

obj.methodB();

Then some guy changed the final to volatile.

...

private volatile Object lock = new Object();

...

The reason from him is:

- Using

volatilehere can avoid any optimizations from system that’s what he wanted. - if there is no

volatilekeyword, there will be two instances in memory due to the CPU cache.

However, I don’t know what’s the optimizations he talked about, but There are at least three mis-understandings here:

- The

lockobject is only used for the stakeholder ofsynchronized. It has nothing other else - which doesn’t need to be re-assigned with another object. There is no update on thislock, but only read. So there is no neccessary to havevolatile, butfinalis MUST to have. - What’s the CPU really caching - which we’ve already went through in this topic, either the copy value of primitive type or the copy of reference(or pointer, but not the object itself which is only stored in heap)

- How does the

synchronizedwork? How does JVM implementsynchronizedinside? We marks a code block withsynchronizedon a reference(e.g.,synchrnoized(lock)), what does that mean? If some codes are below, does thesynchronizedstill work? Team didn’t have a full picture of it.Object objCopy = obj; synchronized(objCopy) { ... }

volatile is a very interesting topic and synchronized is even more. Next time, I would like to spend at least two blogs to introduce synchronized in Java, and the magic CAS - Compare and Swap.